I found Chapters 1 and 2 of Hagen

Schulze’s book to be very interesting, and I enjoyed getting to learn about the origins of Germany and its long road to developing a national

identity of its own. What I found most interesting about Chapter 2 was that the tipping point that

led to the beginning of a national identity for Germany was based on a text called Germania (Schulze, p. 47). I am fascinated by the way that history is presented, and it is clear that historical texts can have a drastic effect on the way people view a nation.

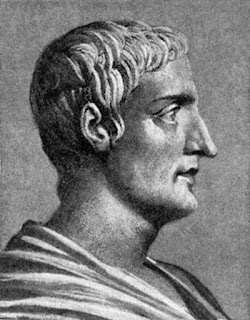

Above is a bust of Tacitus. Tacitus was a respected Roman historian who was responsible for writing Germania for Emperor Trajan in about 100 B.C. Germania was rediscovered by Italian humanist Poggio Bracciolini around 1455 (Schulze, p. 47; "Tacitus", 2004).

As noted by Schulze, no one seemed to consider

whether or not Tacitus "invented or stylized his German paragons..."

although based on that statement, it seems that could have been a possibility

(p. 49). I found it surprising that after Germania, it became common across Europe to create “national myths, ” and was even more surprised to learn that "the consciousness [of the existence of a German nationality] was based on a myth of national origins" (Schulze, p. 50; Schulze, p. 49). After considering the text further, it makes sense that a myth of national origins could have united Germany to a national identity, especially since some foreigners considered the people who would come to be known as Germans "crude, alcohol-sodden barbarians" up until Germania was rediscovered (Schulze, p. 49). Although it was written in 100 B.C., Germania gave Europeans in 1500 confidence that the Germānī people, and therefore, Germans, were "worthy of interest" (Schulze, p. 47).

Undoubtedly some people do not agree with

romanticizing history or creating national myths, and I believe it is important to know the actual

history behind the romanticized version.

However, it is natural to have a self-serving bias for one’s own

nation and to want to paint it in a favorable light even if the truth

is stretched in the process. Clearly, the notion of romanticizing

certain aspects of history was common in Europe at the time, and in reality,

romanticizing history still happens to this day. For example, to

relate this to our own history, some scholars are frustrated with the way that

Americans romanticize Thanksgiving because they feel that doing so falsely

depicts the relationship between the Native Americans and the settlers.

This epoch of creating national myths can be

related to another epoch in German history that was discussed in Chapter

1. Barbarossa (1152-1254) was a hero who was used by Germans in the

nineteenth century as a symbol for their desire to become a nation (Schulze, p.

12). According to Schulze, however, the use of Barbarossa as a symbol “had

more to do with romantic imaginings than the actual Hohenstaufens” (p.

13). For the second time, it seems that romanticizing an aspect of history united Germans, this time in their desire to have a nation.

Pictured above is a painting of Barbarossa by German historical painter Karl Friedrich Lessing. Frederick I (1152-1254), nicknamed "Barbarossa" because of the color of his beard, was a beloved emperor in the Hohenstaufen dynasty (Schulze, p. 12; Birkenstock, 2011).

While Erasmus of Rotterdam found it sad that

nations had such a sense of “self-regard,” as evidenced through Germania, that

sense of self-regard was exactly what Germany needed to develop their sense of

national identity (Schulze, p. 50) As far as what

that says about Germans, I think they needed something to unite them and show

them that they did have a history, and Germania proved just that.

Word Count: 619

Birkenstock, G. (2011, August 8). Retrieved August 25, 2016 from http://www.dw.com/en/barbarossa-the-red-bearded-hero-a-symbol-of-german-unity/a-15338091.

No comments:

Post a Comment