Before watching this video, the main thing that came to mind

when I thought of Berlin was the Berlin Wall, but I realized while watching the

documentary that my knowledge of the Berlin Wall merely scratched the

surface. Therefore, I really enjoyed

getting to learn more about the reasoning behind the existence of the wall. The

Berlin Wall began on “Barbed Wire Sunday” as merely a barbed wire fence

separating Communist East Berlin from Capitalist West Berlin (Part 6: 2:12). East Germany wanted the Berlin Wall to be built in order to prevent

refugees from escaping to the West (Part 4: 6:30).

The barbed wire was followed by a physical wall built that separated East

and West Berlin. Unfortunately, in

certain places, the wall cut right between communities and neighborhoods, in

some cases separating families and lovers, something referred to in the video

as “a psychological catastrophe” (Part 6: 2:57-3:01; Part 11: 8:31). Some people from East Berlin went so far as to

jump out of their windows in an attempt to get to West Berlin (Part 11: 0:40).

Pictured above is Frieda Schulze, a woman who was held back by East Berlin police while trying to jump into West Berlin (Part 11: 0:49) (1).

However, everyone in East Berlin did not want to go to West Berlin. In fact, West Berlin was completely surrounded by the Berlin Wall (Part 11:9:11-9:15). Therefore, West Berliners were “voluntary

prisoners in their own city” (Part 11: 9:20). Additionally, although they lived under communism, East Berlin had a newly built Palace of the Republic, which had "wedge[d] in the hearts of East Berliners" (Part 6: 6:10-6:13). The Palace of the Republic in East Berlin served not only as a Parliamentary seat but also an "open house" for East Berlin citizens (Part 6: 5:48). There, they were able to enjoy social gatherings and live music (Part 6: 5:50-6:02). The Berlin Wall eventually came down in 1989, and overall, citizens rejoiced (Part 13: 1:23).

Pictured above is a map of Berlin and the Berlin Wall in 1961. Clearly, West Berlin is contained entirely within the Berlin Wall (2).

The second topic I found very interesting was the

relationship between Berlin and Jewish people.

I was completely shocked to learn that Jews had actually sought out

Berlin because of the promise of religious freedom in 1685, a promise that was

made in an attempt to bring more people to the city of Berlin (Part 9: 0:52-1:43). While Jews initially had a fairly good

relationship with Berlin despite the fact that they had to pay higher taxes (Part 9: 2:03-2:07),

when Hitler took power, Jews were targeted, many were killed, and their schools as well as their synagogues

were destroyed (Part 9: 5:01-5:22). I also found it

surprising yet incredibly profound that not all Jews wanted to leave Berlin,

even though many were being targeted and killed.

I had always assumed that Jewish people did not leave because they did

not have the means to, and while that probably played a huge role, in

hearing from the Jewish man in the video, it was evident that he did not want

to leave. As he put it simply yet beautifully “This [Berlin] is my home” (Part 9: 10:00). Rather than citing reasons why he did not

leave, he seemed to suggest that for him, leaving was never an option.

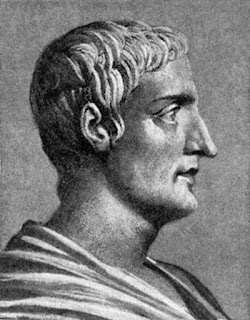

Pictured above is Moses Mendelssohn, a philosopher respected who fought for the equality of Jews and had a Jewish school named after him that was destroyed by the Nazi party (3).

The final topic that interested me and also made me even more

excited for our trip was the high importance that Berliners place on

architecture. Throughout the video, it was clear that architecture represented bigger ideas

than merely just structures. The architecture and what was in the building seemed to

represent certain ideas and power. Architecture seemed to really go hand in hand with the

ideals of the time. For instance, as Germany became one of the world's greatest innovators, the modernism movement was born (Part 7: 6:45). However, when Hitler rose to power, the

Nazi Party deemed modernism “Cosmopolitan rubbish,” and since the Nazi party

was in power, that brought the modernism movement to an end (Part 7: 8:50-8:55).

It was also immensely clear that architecture was closely

tied in to power and politics. "The destruction of old buildings...became a creative and political act" (Part 5: 10:34) One of the most interesting examples of how politics affected architecture was the tearing down of the Schloss Castle by East Berlin since the communist leaders thought it represented "the wrong kind of history" (Part 6: 0:16). East Berlin decided to replace the Schloss in 1973 with The Palace of the Republic, a Parliament building and "open house" for the people of East Berlin (Part 6: 5:35-5:52). Although those in the West were upset by the change, East Berliners overall seemed to really enjoy the space.

Architecture was also used to convey power. For instance, East and West Berlin competed with one another with architecture that "responded to the wall" (Part 6: 3:29). A police headquarters was built right next to the wall on the side of West Berlin, and in response, East Berlin built four apartment buildings that overcast the police headquarters (Part 6: 3:44-4:16). Perhaps the greatest achievement of the "competition" was the TV tower built in East Germany that became an icon of the city, and was able to be seen from over the wall (Part 6: 4:30). In addition to the battle for power between East and West Berlin, Hitler also tried to use architecture to gain power. Though they were never realized, he had plans drawn up by his architect of a capital Germania which was meant to be so huge that it would “dwarf everything in it and around it" (Part 7: 10:55). I am excited to learn more about architecture on our trip and how it was used both to convey messages and as a symbol of power.

Pictured above are the plans created by Hitler's architect, Speer, for his capital of Germania (4).

Word Count: 855

Image sources:

(1) http://www.berliner-mauer-gedenkstaette.de/en/uploads/historischer_ort_bilder/histort_flucht_f_schulze_ullstein_0101.jpg

(2) http://image.slidesharecdn.com/day1pp-100218122352-phpapp01/95/berlin-wall-15-728.jpg?cb=1266495887

(3) http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/biography/Mendelssohn.html

(1) http://www.berliner-mauer-gedenkstaette.de/en/uploads/historischer_ort_bilder/histort_flucht_f_schulze_ullstein_0101.jpg

(2) http://image.slidesharecdn.com/day1pp-100218122352-phpapp01/95/berlin-wall-15-728.jpg?cb=1266495887

(3) http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/biography/Mendelssohn.html

(4) http://www.strangehistory.net/blog/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/germania-hitler%C3%ACs-capital.jpg